A new series of articles entitled "From the pages of the college history..." will appear from now on.

'Scorpius' is going to bring out the rich culture and tradition of our Alma mater "The American College" in this series of well researched articles. You are welcome to send your feedback.

-peakay

Commemorating Tagore and his visit to the American college

Part – I: Public Intellectuals, Liberal educators and the Public Domain

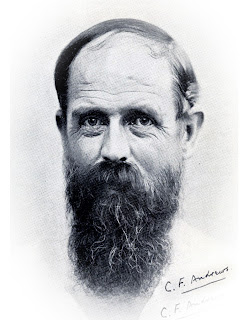

|

| Tagore (1861-1941) |

London, Darlington, Cambridge and Birmingham in the U.K., Stockholm, Leiden, Barcelona and Salamanca in Europe, Washington and Chicago in the U.S., Singapore and Kualalampur in the South East Asia are some places outside India that fashionably figured in the show. Tagore, the first non-European Nobel laureate who earned the 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature, by the standards of his time was a globetrotter. He had visited most of the towns and cities mentioned above and had not failed to leave some memory traces, however vague and distant. That was enough for Tagore enthusiasts and the Diaspora to pick the thread up.

Back here in the sub-continent the most fitting tribute came from Shaik Hasina, the Prime Minister of Bangladesh, herself a Tagore admirer, announced the setting up of Rabindra University at Shilaidaha [now in Bangladesh], where the Bengali polymath spent most part of his creative life. This is certainly an acknowledgement of Tagore’s contribution to Bangladeshi nationalism despite growing Islamisation and India-phobia.

Within India, beyond Bholpur (Shantiniketan), Calcutta, Delhi, Ahmadabad, Hyderabad and Mumbai not much is heard in terms of Tagore commemorations. Though Tagore stands out easily as a national icon, he does not make a big emotional appeal in general. This is partly because of the kind of controversies he brooked from the early days as a public intellectual, especially with the nationalist including Gandhi allowing himself to be branded as too idealistic arrogant and even unpatriotic, and partly because of his strong regional identity as a Bengali poet/writer. If his non-Bengali admirers would give him the maximum allowance as one who made stupendous contribution to late Bengali renaissance, those who suffer anglophilia would not concede him the status as an Indian writer in English. Even his own translation of Gitanjali into English and the consequent award of Nobel Prize and his late English writings did not rehabilitate him of this Image. Then there lies the general apathy. Ashok Mitra in a commemorative article recently said, “When the man once hailed as the Father of Nation is not little more than a half-forgotten totem, Tagore could hardly expect a better treatment”. But Tagore certainly needs a better treatment as so much lies undeciphered beyond his poetic and artistic persona.

Now let me turn my attention to the little known story of the visit to American College by Tagore and his very close friend and associate C. F. Andrews in February-March 1919. This I choose not to do, merely as an attempt to leave simply another commemorative signature of Madurai, which town the poet set his foot on as a celebrity. But by re-telling the little known story of Tagore’s visit, I try to open up a window that would allow us a few glimpses of the grand old days when liberal institutions like the American College were founded and shaped. The chief architects of these vintage institutions were either public intellectuals like Tagore, C. F. Andrews and Sushil K. Rudra of St. Stephen’s, Delhi or liberal educators like W. M. Zumbro of The American College or who saw educational institutions as part of the public domain. This means that the latter saw that the institutions they raised, had a definite role to play in the shaping of the public sphere. This is the reason why liberal institutions were not only eager to associate and interact with public intellectuals but also organized public lectures as their higher calling. When you scratch the surface to get into the story of Tagore’s visit to the American College, a fascinating network of relationship of great public personalities, at times extending to deep friendship opens up. W.M. Zumbro the chief architect of the American College should have known C.F. Andrews well. Andrews’ legendry friendship with both Tagore and Mahatma Gandhi does not need elaboration. What is not well known however is that like Zumbro, Andrews was a liberal Christian missionary-educator from the west, later turned out to become one of the most admired public intellectuals of pre-independent India. During his initial years, Andrews worked to shape St. Stephen’s at Delhi before joining Tagore at Shantiniketan. Equally less talked about is, Mahatma Gandhi’s association with St. Stephen’s and the kind of public consequences the friendship of the trio – Rudra, Andrews and Gandhi brought for India.

|

| W.M.Zumbro (1865-1922 |

At the cost of digression, I want to elaborate a little on the St. Stephen’s story. Rev. C. F. Andrews was an ordained priest of the Cambridge Mission supported by the SPG who was teaching philosophy at Pembroke College, Cambridge. When the post of Principal of St. Stephen’s fell vacant after Rev. G. Hibbert Ware, it was Sushil Rudra, Vice-Principal then at St. Stephen’s, wrote to Cambridge Brotherhood inviting Andrews to take over as its Principal. But Andrews found Rudra to be the most suited person for the job, and after much persuasion of the Home Mission, Andrews succeeded in getting him appointed as

the Principal. Sushil Kumar Rudra was not only the first Indian Principal of St. Stephen’s but also possibly was the first Indian to be appointed to the position of the Principal at a mission college. Rudra, a Bengali Christian of CMS background, a man of great faith, started his life as a liberal, teaching English at St. Stephen’s. But his love for the nation made him a true public intellectual and he made no secret of even his sympathies for the extremists who fought for the national cause. This transformation of Rudra from being a liberal Christian into a public intellectual daring to take open political stands, is noteworthy. Many might not know that it was Rudra who was primarily responsible for bringing Mahatma Gandhi to India from South Africa. The following account of Ajit Rudra, his son, to the veteran journalist Bruce Williams, quoted in Susan Viswanathan’s article would tell us what kind of a public personality he was.

“I first heard the name Gandhi fall from my father’s lips in 1913. It was at breakfast. My father was very excited, anxiously awaiting Andrews’ appearance. ‘Have you read today’s leading article?’, he asked Andrews when he arrived. ‘It is about this man Gandhi, working for Indians in South Africa. It seems he is very courageous, he shows sign of leadership. He appears ready to sacrifice himself for the country….’All the intelligentsia of Delhi used to meet at St. Stephen’s college to discuss the important question of the days with the faculty and some of the senior students. So my father became well known as one of India’s first civil rights leaders… He [Rudra] and nobody else sent Andrews to South Africa. And Andrews brought Gandhi back to India. No one seems to recognize that Gandhi lived as my father’s guest off and on for eleven years. None of those who run the country today would give my father any credit for this”.

|

| C.F.Andrews (1871-1940) |

|

| S.K.Rudra (1861-1925) |

On the instigation of Rudra, C. F. Andrews and W. W. Pearson (another Tagore associate at Shantiniketan) left for South Africa and spent days and months in Gandhi’s camps before they persuaded him to shift to India. Between 1915 and 1923, Gandhi whenever he visited Delhi, was always a guest at Principal’s residence at Stephen’s. When the Imperial Government at Delhi expressed its displeasure as things became politically too hot after the Khilafat Movement (1919) and the first Non-Cooperation Movement (1920), Rudra daringly stood his ground saying, “It does not lie in my heart to close my door in the face of a friend.” Gandhi, whenever he stayed with Rudra at St. Stephen’s, discussed seriously political issues with Rudra, addressed students, attended regularly the Chapel fond of singing ‘abide with me’ and ‘lead kindly light’ and quietly spent his time in Rudra’s study.

|

| M.K. Gandhi (1869-1948) |

Gandhi however was not mean like the present day politicians. He honestly acknowledged Rudra’s political contribution. When Rudra died in 1924, Gandhi wrote in young India, “… my open letter to the Viceroy, giving concrete shape to the Khilafat claim, was conceived and drafted under Principal Rudra’s roof. He and Charlie Andrews were my revisionists. Non-Cooperation was conceived and hatched under his hospitable roof…” Such was the influence of a publicly minded Christian educationist of Delhi and the publicness he brought into the educational sphere. Rudra when he thought of bringing Gandhi to India, would not have imagined that it would completely change the destiny of a nation.

Reviving the old bond. Both American College & St.Stephen's were started in the same year in 1881. After Andrews, it was Anil Wilson the 11th Principal of Stephen's visited American College after a gap of about 90 years.Anil is received by Principal Chinnaraj on the 127th College Day.

C. F. Andrews from the beginning was in open rebellion with the English ruling class. He was always fond of saying, “... British talk about being ‘trustees of India’, and coming over 'to serve her', about bearing the ‘whiteman’s burden’, about ruling India for ‘her good’ and all the rest of hypocrisy on God’s earth”. He continued with Stephen’s till 1914 as its Vice-Principal. Apart from making Sushil the first Indian Principal, Andrews was keen to decentralize and secularize the college and was instrumental in drafting the new constitution for the college ensuring more autonomy for the college from the Church. He went to England along with Rudra to defend it before the Mission. He continued with his role as an activist whether it came to the issue of indentured labour in British colonies or fighting for the cause of mill workers within India. This earned him the name Deenabandhu (Friend of the suffering). In 1912, Andrews met Tagore in the house of William Rothenstein, who first read Tagore’s manuscript of Gitantjali and introduced him to thinkers, painters and poets including W. B. Yeats. Attracted by the poet, Andrews left Stephen’s in 1914, to work for Shantiniketan. He was involved in editing various Tagore publications and for sometime acted as his representative to Macmillan Publishing. Thus in a liberal Christian missionary-educationist, we see an exemplary model of a public intellectual. He was pivotal in bringing together in a lovely bond of friendship all the great souls of the time – Rudra, Gandhi, Tagore and Pearson. In his death bed at Calcutta, he whispered in the ears of Gandhi, “Mohan, Swaraj is coming.”

Groomed by Michigan , Yale and Columbia , W.M. Zumbro, an American Congregationalist became the second principal of the American College Madurai

“The influence of any well organized College should make its influence felt in two ways. It should have a very direct influence upon the students who are gathered within it . . . .

But a college has, or ought to have another strong influence in the city where it is located. The college comes to be after a time identified in a way with the city. Its halls are open for lectures where the best men of the time are heard. The interest and life become in a measure bound up with the city. Not only through lectures and general meetings is this influence felt, but the college societies, the Y.M.C.A., the debating society, and other organizations which find a place within the college all help in extending this influence, and increasing the opportunity which the college has of moulding the life of the people and this can only be secured after years of successful and helpful work”

In sum, the college apart from moulding students, ought to mould the life of the people in the city. Compared to other protagonists, Zumbro sounds cautiously more civic than political in opening up the public domain of education.

Whatever be their religious background or political purpose, these men of liberal pursuit were seriously obsessed with the public domain because the larger responsibility of education, for them, was to change the society.

Whatever be their religious background or political purpose, these men of liberal pursuit were seriously obsessed with the public domain because the larger responsibility of education, for them, was to change the society.Tagore’s visit to American College was definitely not an ostentatious visit of a celebrity. The college in fact intended to have a sustained relationship with the poet. Professor Saunders, then editor of The American College Magazine reports:

“We had hoped to have, in fact one was arranged but had to be abandoned owing to the poet’s indisposition, a conference between Sir Rabindranath Tagore and many of the educationalists of Madura when this [Shantiniketan] scheme and other suggestions would have been thoroughly considered. We are extremely sorry that the conference could not be held”

Tagore's visit to the American College March 1919

But C.F.Andrews came first in February 1919 preparing the ground for Tagore’s visit. He spoke in detail about the Shantiniketan model about which Saunders reported: “The college was eager to learn more” [This will be dealt in greater detail in Part-II of this essay]

Tagore came in March 1919. He was still Sir Rabindranath Tagore. Jallian Wallabagh massacre would take place in a few days. Tagore would renounce his knighthood in protest against the killings. He stayed for three days and gave three lectures: The Message of the Forest, The Spirit of Popular Religion in India

It is not a surprise Zumbro, the man of public domain, later wrote in his report, “The most important event in our college during the year aside from routine work, and the largest contribution which the college made to the public, was securing India’s great poet Rabindranath Tagore to give a series of lectures …. The presence of the poet was a benediction to the whole town ….”

It is no flaunting when we say, “Madurai grew with American College and American College grew with Madurai

(To be continued)

SCORPIUS

0 comments :

Post a Comment